Genocide

The longest and quite possibly the most important article that The Sunday Times has ever printed

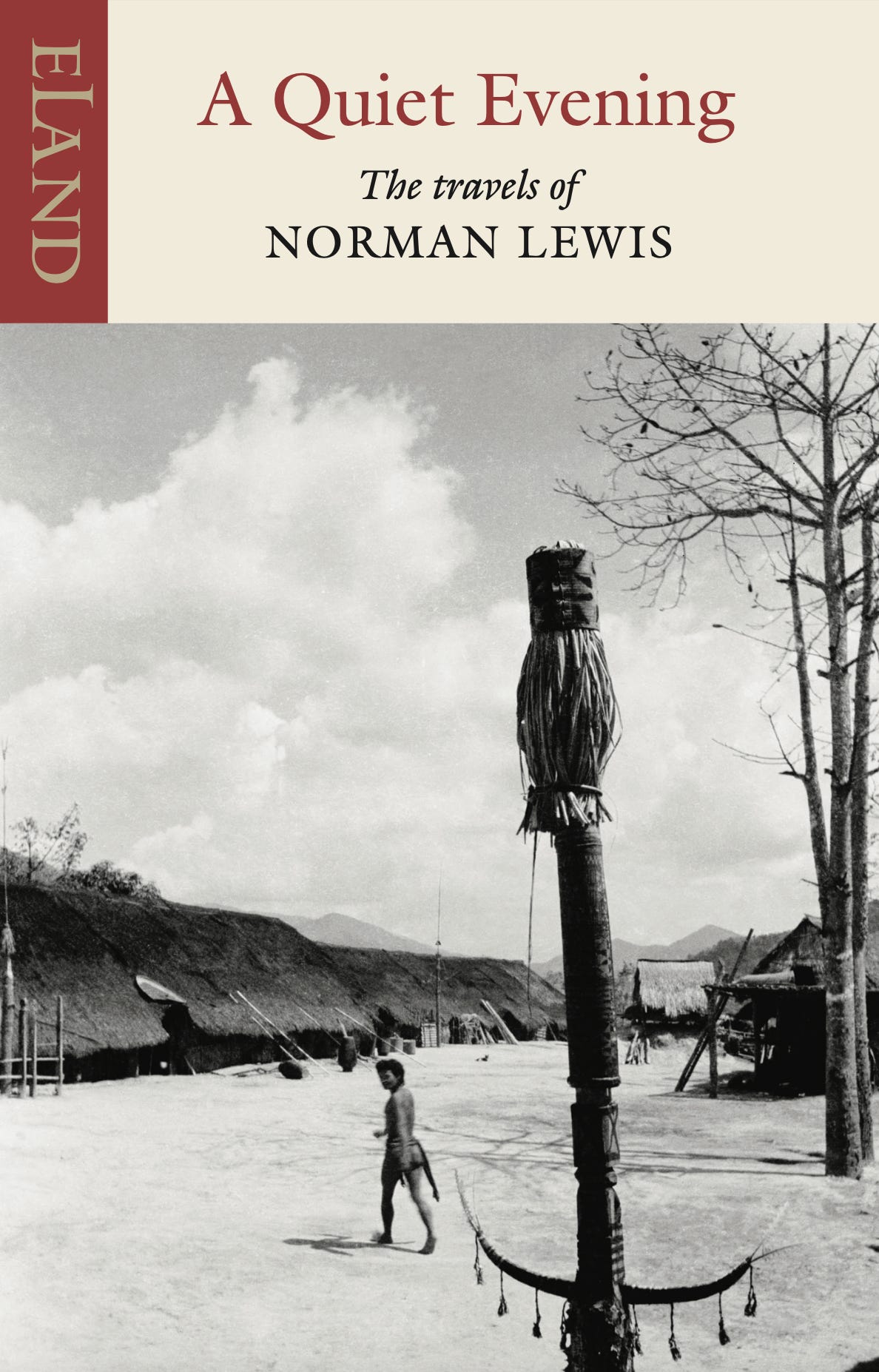

Genocide appears in Eland’s new collection of Norman Lewis’ travel writing, A Quiet Evening, selected and introduced by the veteran publisher, John Hatt

In 1968 Lewis approached The Sunday Times after he learnt that the Indian Protection Service in Brazil had been complicit in the murderous destruction of Indian communities. The paper agreed to send him and, after spending several weeks in Brazil, he returned to England to write a 12,000-word article. This was the longest article that The Sunday Times magazine had ever printed.

As soon as the piece was published, the tremendous interest obliged the paper to hire extra staff to handle the copious correspondence and telephone calls. One of those who contacted the paper was Robin Hanbury-Tennison, who promptly founded Survival International, which campaigns with indigenous peoples worldwide.

On this trip, Lewis travelled without a photographer. After returning, he made a list of places for a photographer to visit. The Sunday Times sent out a young photographer, Don McCullin, who had made his name in Vietnam and Biafra. Lewis was so impressed by McCullin’s photographs that he asked to meet him, and thus began a long and fruitful friendship.

A useful summary of the current predicament for Brazilian’s indigenous population can be found by googling ‘Brazilian Indigenous people survival international pdf’. The article is illustrated with some of McCullin’s remarkable photographs, and lists valuable links for further information, including about the ever-continuing assaults on indigenous communities.

Lewis considered this article the most important of his lifetime. John Hatt, Founding Publisher of Eland

First published in The Sunday Times, February 23, 1969

If you happened to be one of those who felt affection for the gentle, backward civilisations – Nagas, Papuans, Mois of Vietnam, Polynesian and Melanesian remnants – the shy primitive peoples, daunted and overshadowed by the juggernaut advance of our ruthless age, then 1968 was a bad year for you.By the descriptions of all who had seen them, there were no more inoffensive and charming human beings on the planet than the forest Indians of Brazil, and brusquely we were told they had been rushed to the verge of extinction. The tragedy of the Indian in the United States in the last century was being repeated, but it was being compressed into a shorter time. Where a decade ago there had been hundreds of Indians, there were now tens. An American magazine reported with nostalgia on a tribe of which only 135 members had survived. “They lived as naked as Adam and Eve in the nightfall of an innocent history, catching a few fish, collecting groundnuts, playing their flutes, making love ... waiting for death. We learned that it was due only to the paternal solicitude of the Brazilian Government’s Indian Protection Service that they had survived until this day”.

In all such monitory accounts – and there had been many of them – there was a blind spot, a lack of candour, a defect in social responsibility, an evident aversion to pointing to the direction from which doom approached. It seemed that we were expected to suppose that the Indians were simply fading away, killed off by the harsh climate of the times, and we were invited to inquire no further. It was left to the Brazilian Government itself to resolve the mystery, and in March 1968 it did so, with brutal frankness, and with almost no attempt at self-defence. The tribes had been virtually exterminated, not despite all the efforts of the Indian Protection Service, but with its connivance – often its ardent co-operation.

General Albuquerque Lima, the Brazilian Minister of the Interior, admitted that the Service had been converted into an instrument for the Indians’ oppression, and had therefore been dissolved. There was to be a judicial inquiry into the conduct of 134 functionaries. A full newspaper page in small print was required to list the crimes with which these men were charged. Speaking informally, the Attorney General, Senhor Jader Figueiredo, doubted whether ten of the Service’s employees out of a total of over a thousand would be fully cleared of guilt.

The official report was calm – phlegmatic almost – all the more effective therefore in its exposure of the atrocity it contained. Pioneers leagued with corrupt politicians had continually usurped Indian lands, destroyed whole tribes in a cruel struggle in which bacteriological warfare had been employed, by issuing clothing impregnated with the virus of smallpox, and poisoning food supplies. Children had been abducted and mass murder gone unpunished. The Government itself was blamed to some extent for the Service’s increasing starvation of resources over a period of thirty years. The Service had also had to face ‘the disastrous impact of missionary activity’.

Next day the Attorney General met the Press, and was prepared to supply all the details. A commission had spent 58 days visiting Indian Protection Service posts all over the country collecting evidence of abuses and atrocities.

The huge losses sustained by the Indian tribes in this tragic decade were catalogued in part. Of 19,000 Munducurus believed to have existed in the 1930s, only 1,200 were left. The strength of the Guaranis had been reduced from 5,000 to 300. There were 400 Carajas left out of 4,000. Of the Cintas Largas, who had been attacked from the air and driven into the mountains, possibly 500 had survived out of 10,000. The proud and noble nation of the Kadiweus – ‘the Indian Cavaliers’ – had shrunk to a pitiful scrounging band of about two hundred. Only a few hundred remained of the formidable Chavantes who prowled in the background of Peter Fleming’s Brazilian Journey, but they had been reduced to mission fodder – the same melancholy fate that had overtaken the Bororos, who helped to change Lévi-Strauss’s views on the nature of human evolution. Many tribes were now represented by a single family, a few by one or two individuals. Some, like the Tapaiunas had disappeared altogether – in this case from a gift of sugar laced with arsenic. It is estimated that only between 50,000 and 100,000 Indians survive today.

Senhor Figueiredo estimated that property worth 62 million dollars had been stolen from the Indians in the past ten years.

He added, ‘It is not only through the embezzlement of funds, but by the admission of sexual perversions, murders and all other crimes listed in the penal code against Indians and their property, that one can see that the Indian Protection Service was for years a den of corruption and indiscriminate killings.’ The head of the service, Major Luis Neves, was accused of 42 crimes, including collusion in several murders, the illegal sale of lands, and the embezzlement of 300,000 dollars. Senhor Figueredo informed the newspapermen that the documents containing the evidence collected by the Attorney General weighed 103 kilograms, and amounted to a total of 5,115 pages.

In the following days there were more headlines and more statements by the Ministry:

Rich landowners of the municipality of Pedro Alfonso attacked the tribe of Craos and killed about a hundred.

The worst slaughter took place in Aripuaná, where the Cintas Largas Indians were attacked from the air using sticks of dynamite.

The Maxacalis were given fire-water by the landowners who employed gunmen to shoot them down when they were drunk.

Landowners engaged a notorious pistoleiro and his band to massacre the Canelas Indians.

The Nhambiquera Indians were mown down by machine-gun fire.

Two tribes of the Patachós were exterminated by giving them smallpox injections.

In the Ministry of the Interior it was stated yesterday that crimes committed by certain ex-functionaries of the IPS amounted to more than a thousand, ranging from tearing out Indians’ finger-nails to allowing them to die without any relief.

To exterminate the tribe Beiços de Pau, Ramis Bucair, Chief of the 6th Inspectorate, explained that an expedition was formed which went up the River Arinos carrying presents and a great quantity of foodstuffs for the Indians. These were mixed with arsenic and formicides.... Next day a great number of the Indians died, and the whites spread the rumour that this was the result of an epidemic.

As ever, the frontiers with Colombia and Peru (scene of the piratical adventures of the old British-registered Peruvian Amazon Company) gave trouble. A minor boom in wild rubber set off by the last war had filled this area with a new generation of men with hearts of flint. In the 1940s one rubber company punished those of their Indian slaves who fell short in their daily collection by the loss of an ear for the first offence, then the loss of the second ear, then death. When chased by Brazilian troops, they simply moved, with all their labour, across the Peruvian border. Today, most of the local landowners are slightly less spectacular in their oppressions. One landowner is alleged to have chained lepers to posts, leaving them to relieve themselves where they stood, without food or almost any water for a week. He was a bad example, but his method of keeping the Ticuna Indians in a state of slavery was the one commonly in use. They were paid half a cruzeiro for a day’s labour and then charged three cruzeiros for a piece of soap. Those who attempted to escape were arrested (by the landowner’s private police force) as thieves.

Senhora Neves da Costa Vale, a delegate of the Federal Police who investigated this case, and the local conditions in general, found that little had changed since the bad old days. She noted that hundreds of Indians were being enslaved by landowners on both sides of the frontier, and that Colombians and Peruvians hunted for Ticuna Indians up the Brazilian rivers. Semi-civilised Indians, she said, were being carried off for enrolment as bandits in Colombia. The area is known as Solimões, from the local name of the Amazon, and Senhora Neves was shocked by the desperate physical condition of the Indians. Lepers were plentiful, and she confirmed the existence of an island called Armaça, where Indians who were old or sick were concentrated to await death. She said that they were without assistance of any kind.

From all sources it was a tale of disaster. No one knew just how many Indians had survived, because there was no way of counting them in their last mountain and forest strongholds. The most optimistic estimate put the figure at 100,000, but others thought they might be as few as half this number. Nor could more than the roughest estimate be made of the speed of the process of extermination. All accounts suggest that when the Europeans first came on the scene four centuries ago they found a dense and lively population. Fray Gaspar, the diarist of Orellana’s expedition in 1542, claims that a force of fifty thousand once attacked their ship. At that time the experts believe that the Indians may have numbered between three and six million. By 1900, the same authorities calculate, there may have been a million left. But in reality, it is all a matter of guesswork.

The first Europeans to set eyes on the Indians of Brazil came ashore from the fleet of Pedro Álvares Cabral in the year 1500 to a reception that enchanted them, and when the ships set sail again they left with reluctance.

Pêro Vaz de Caminha, official clerk to the expedition, sent off a letter to the King that crackled with enthusiasm. It was the fresh-eyed account of a man released from the monotony of the seas to miraculous new experiences that might have been written to any crony back in his hometown. Nude ladies had paraded on the beach splendidly indifferent to the stares of the Portuguese sailors – and Caminha took the King by the elbow to go into their charms at extraordinary length. The Indian girls were fresh from bathing in the river and devoid of body hair. Caminha describes their sexual attractions with minute and sympathetic detail adding that their genitalia would put any Portuguese lady to shame. In those days Europeans rarely washed (a treatise on the avoidance of lousiness was a best seller), so one supposes that the Portuguese were frequently verminous in these regions. Caminha cannot avoid coming back to the subject again before settling to prosaic details of the climate and produce of the newly discovered land. ‘Sweet girls,’ he says.... ‘Like wild birds and animals. Lustrous in a way that so far outshines those in captivity – they could not be cleaner, plumper and more vibrant than they are.’

The Europeans were overwhelmed, too, by the magnificence of the Indians’ manners. If they admired any of the necklaces or personal adornments of feathers or shells these were instantly pressed into their hands. In other encounters it was to be the same with golden trinkets, and temporary wives were always to be had for the taking. The bolder of the women came and rubbed themselves against the sailors’ legs, showing their fascination at the instant and unmistakable sexual response of the white men.

Such open-handedness was dazzling to these representatives of an inhibited but fanatically acquisitive society. The official clerk filled page after page with a catalogue of Indian virtues. All that was necessary to complete this image of the perfect human society was a knowledge of the true God. And since these people were not circumcised, it followed that they were not Mohammedans or Jews, and that there was nothing to impede their conversion. When the first Mass was said the Indians, with characteristic politeness and tact, knelt beside the Portuguese and, in imitation of their guests, smilingly kissed the crucifixes that were handed to them. As discussion was limited to gestures the Portuguese suspected their missionary labours were incomplete, and when the fleet sailed, two convicts were left behind to attend to the natives’ conversion.

It was Caminha’s letter that encouraged Voltaire to formulate his theory of the Noble Savage. Here was innocence – here was apparent freedom, even, from the curse of original sin. The Indians, said the first reports, knew of no crimes or punishments. There were no hangmen or torturers among them; no destitute. They treated each other, their children – even their animals – with constant affection. They were to be sacrificed to a process that was beyond the control of these admiring visitors. Spain and Portugal had become parasitic nations who could no longer feed themselves.

The fertile lands at home had been abandoned, the irrigation systems left by the Moors were fallen into decay, the peasants dragged away to fight in endless wars from which they never returned. Economic forces that the newcomers could never have understood were about to transform them into slavers and assassins. The natives gave gracefully, and the invaders took what they offered with grasping hands, and when there was nothing left to give the enslavement and the murder began. The American continent was about to be overwhelmed by what Claude Lévi-Strauss described four hundred years later as ‘that monstrous and incomprehensible cataclysm which the development of Western civilisation was for so large and innocent a part of humanity.’

Caminha and his comrades landed at Porto Seguro, about five hundred miles up the coast from the present Rio de Janeiro, and it is no more than a coincidence that a handful of Indians have somehow succeeded in surviving to this day at Itabuna, which is nearby. The continued presence of these Tapachós is something of a mystery, because for four centuries the area has been ravaged by slavers, belligerent pioneers and bandits of all descriptions. The survivors are found in a swarthy, austere landscape, hiding in the ligaments of bare rock, in the crevices of which they have developed an aptitude for concealment; furtive creatures in tropical tatters, scuttling for cover as they are approached. One sees them in patches of wasteland by the roadside or railway track, which they fertilise by their own excrement to grow a few vegetables before moving on. Otherwise they eke out a sub-existence by selling herbal recipes and magic to neurotic whites who visit them in secret, also by a little prostitution and a little theft. They suffer from tuberculosis, venereal disease, ailments of the eye, and from epidemics of measles and influenza, the last two of which adopt particularly lethal forms.

Two of their tribes held on through thick and thin to a little of their original land until ten years ago when a doctor – now alleged to have been sent by the Indian Protection Service of those days – instead of vaccinating them, inoculated them with the virus of smallpox. This operation was totally successful in its aim, and the vacant land was immediately absorbed into the neighbouring white estates.

There are a dozen such dejected encampments along three thousand miles of coastline, and they are the last of the coastal Indians of the kind seen by Caminha, who once appeared from among the trees by their hundreds whenever a ship anchored offshore. The Patachós are officially classified as integrados. It is the worst label that can be attached to any Indian, as extinction follows closely on the heels of integration.

The atrocities of the conquistadores described by Bishop Bartolomeo de Las Casas, who was an eyewitness of what must have been the greatest of all wars of extermination, resist the imagination. There is something remote and shadowy about horror on so vast a scale. Numbers begin to mean nothing, as one reads with a sort of detached, unfocused belief of the mass burnings, the flaying, the disembowelling, and the mutilations.

Some twelve million were killed, according to Las Casas, most of them in frightful ways. ‘The Almighty seems to have inspired these people with a meekness and softness of humour like that of lambs; and the conquerors who have fallen upon them so fiercely resemble savage tigers, wolves and lions.... I have seen the Spaniards set their fierce and hungry dogs at the Indians to tear them in pieces and devour them.... They set fire to so many towns and villages it is impossible I should recall the number of them.... These things they did without any provocation, purely for the sake of doing mischief.’ Wherever they could be reached, in the Caribbean islands, and on the coastal plains, the Indians were exterminated. Those of Brazil were saved from extinction by a tropical rainforest, as big as Europe, and to the south of it, the half million square miles of thicket and swampland – the Mato Grosso – that remained sufficiently mysterious for quite recent explorers, such as Colonel Fawcett, to lose their lives searching for golden cities.

For those who pursued the Indians into the forest there are worse dangers to face than poison-tipped arrows. Jiggers deposited their eggs under their skin; there was a species of fly that fed on the surface of the eye and could produce blindness; bees swarmed to fasten themselves to the traces of mucus in the nostrils and at the corners of the mouth; fire ants could cause temporary paralysis, and worst of all, a tiny beetle sometimes found in the roofs of abandoned huts might drop on the sleeper to administer a single fatal bite.

There were also the common hazards of poisonous snakes, spiders and scorpions in variety, and the rivers contained not only piranhá, electric eels and sting-rays, but also a tiny catfish with spiny fins which allegedly wriggled into the human orifices. Above all, the mosquitoes transmitted not only malaria, but the yellow fever endemic in the blood of many of the monkeys. The only non-Indians to penetrate the ultimate recesses of the forest were the black slaves of later invasions, who escaped in great numbers from the sugar estates and mines to form the quilombas, the fugitive slave settlements. But these, apart from helping themselves to Indian women, where they found them, followed the rule of live and let live. They merged with the surrounding tribes, and lost their identity.

The processes of murder and enslavement slowed down during the next three centuries, but did so because there were fewer Indians left to murder and enslave. Great expeditions to provide labour for the plantations of Maranhão and Pará depopulated all the easily accessible villages near the main Amazonian waterways, and the loss of life is said to have been greater than that involved in the slave trade with Africa. Those who escaped the plantations often finished in the Jesuit reservations – religious concentration camps where conditions were hardly less severe, and trifling offences were punished with terrible floggings or imprisonment: ‘The sword and iron rod are the best kind of preaching,’ as the Jesuit missionary José de Anchieta put it.

By the nineteenth century some sort of melancholy stalemate had been reached. Indian slaves were harder to get, and with the increasing rationalisation of supply and the consequent fall in cost of black slaves from West Africa – who in any case stood up to the work more robustly – the price of the local product was undercut. As the Indians became less valuable as a commodity, it became possible to see them through a misty Victorian eye, and at least one novel about them was written, swaddled in sentiment, and in the mood of The Last of the Mohicans. A more practical viewpoint reasserted itself at the time of the great rubber boom at the turn of the century, when it was discovered that the harmless and picturesque Indians were better equipped than black slaves to search the forests for rubber trees. While the eyes of the world were averted, all the familiar tortures and excesses were renewed, until with the collapse of the boom and the revival of conscience, the Indian Protection Service was formed.

In the raw, abrasive vulgarity that it displayed in its consumption of easy wealth, the Brazilian rubber boom surpassed anything that had been seen before in the Western world since the days of the Klondike. It was centred on Manaus which had been built where it was at the confluence of two great, navigable rivers, the Amazon and the Rio Negro, for its convenience in launching slaving expeditions. It was a city that had fallen into a decline that matched the wane in interest for its principal commodity.

With the invention of the motorcar and the rubber tyre, and the recognition that the hevea tree of the Amazon produced incomparably the best rubber, Manaus was back in business, converted instantly to a tropical Gomorrah. Caruso refused a staggering fee to appear at the opera house, but Madame Patti accepted. There were Babylonian orgies of the period, in which courtesans took semi-public baths in champagne, which was also awarded by the bucketful to winning horses at the races. Men of fashion sent their soiled linen to Europe to be laundered. Ladies had their false teeth set with diamonds, and among exotic importations was a regular shipment of virgins from Poland.

The most dynamic of the great rubber corporations of those days was the British-registered Peruvian Amazon Company, operating in the ill-defined north-western frontier of Brazil, where it could play off the governments of Colombia, Peru and Brazil against each other, all the better to establish its vast, nightmarish empire of exploitation and death.

A young American engineer, Walter Hardenburg, carried accidentally in a fit of wanderlust over the company’s frontier, was immediately seized and imprisoned for a few days during which time he was given a chance to see the kind of thing that went on. Several thousand Huitoto Indians had been enslaved and at the post where Hardenburg was held, El Encanto (Enchantment), he saw the rubber tappers bringing back their collection of latex at the end of the day. Their bodies were covered with great raised weals from the overseers’ tapir-hide whips, and Hardenburg noticed that the Indians who had managed to collect their quota of rubber danced with joy, whereas those who had failed to do so seemed terror-stricken, although he was not present to witness their punishment. Later he learned that repeated deficiencies in collection could mean a sentence of a hundred lashes, from which it took as much as six months to recover.

An element of competition was present when it came to killing Indians. On one occasion one hundred and fifty hopelessly inefficient workers were rounded up and slashed to pieces by macheteiros employing a grisly local expertise, which included the corte do bananeiro, a backward and forward swing of the blade which removed two heads at one blow, and the corte maior, which sliced a body into two or more parts before it could fall to the ground. High feast days, too, were celebrated by sporting events when a few of the more active – and therefore more valuable – tappers might be sacrificed to make an occasion. They were blindfolded and encouraged to do their best to escape while the overseers and their guests potted at them with their rifles.

Barbadian British subjects were recruited by the Peruvian Amazon Company as the hunters of wild Indians, being sent on numerous expeditions into those areas where the company proposed to establish new rubber trails. These were paid on the basis of piecework and were obliged to collect the heads of their victims, and return with them as proof of their claims to payment. Stud farms existed in the area where selected Indian girls would breed the slave-labour of the future when the wild Indian had been wiped out. Some rubber companies have been suspected, too, of not stopping short of cannibalism, and there were strong rumours of camps in which ailing and unsatisfactory workers were used to supply the tappers’ meat.

The worldwide scandal of the Peruvian Amazon Company, exposed by Sir Roger Casement, coincided with the collapse of the rubber boom caused by the competition of the new Malayan plantations, and a crisis of conscience was sharpened by the threat of economic disaster. The instant bankruptcy of Manaus was attended by spectacular happenings. Sources of cash suddenly dried up, and the surplus population of cardsharpers, adventurers and whores poured into the river steamers in the rush to escape to the coast. They paid for the passages with such possessions as diamond cufflinks and solitaire rings. Merchant princes with their fortunes tied up in unsaleable rubber committed suicide. The celebrated electric street cars – first of their kind in Latin America – came suddenly to a halt as the power was cut off, and were set on fire by their enraged passengers. A few racehorses found themselves between the shafts of converted bullock carts. The opera house closed, never to open again.

When the Brazilians had got used to the idea that their rubber income was substantially at an end, they began to examine the matter of its cost in human lives in the light of the fact, now generally known, that the Peruvian Amazon Company alone had murdered nearly thirty thousand Indians. Brazil was now Indian-conscious again and its legislators reminded each other of the principles so nobly enunciated by José Bonifacio in 1823, and embodied in the constitution: ‘We must never forget,’ Bonifacio said, ‘that we are usurpers, in this land, but also that we are Christians.’

It was a mood responsible for the determination that nothing of this kind should ever happen again, and an Indian Protection Service – unique and extraordinary in its altruism in the Americas – was founded in 1910 under the leadership of Marshall Rondon, himself an Indian, and therefore, it was supposed, exceptionally qualified to be able to interpret the Indian’s needs.

Rondon’s solution was to integrate the Indian into the mainstream of Brazilian life – to educate him, to change his faith, to break his habit of nomadism, to change the colour of his skin by inter-marriage, to draw him away from the forests and into the cities, to turn him into a wage-earner and a voter. He spent the last years of his life trying to do this, but just before his death came a great change of heart. He no longer believed that integration was to be desired. It had all been, he said now, a tragic mistake.

The conclusion of all those who have lived among and studied the Indian beyond the reach of Western civilisation is that he is the perfect human product of his environment – from which it should follow that he cannot be removed without calamitous results. Ensconced in the forest in which his ancestors have lived for thousands of years, he is as much a component of it as the tapir and the jaguar: self-sufficient, the artificer of all his requirements, integrated with his surroundings, deeply conscious of his place in the living patterns of the visible and invisible universe.

It is admitted now that the average Indian Protection Service official recruited to deal with this complicated but satisfactory human being was all too often venal, ignorant and witless. It was inevitable that he should call to his aid the missionaries who were in Brazil by the thousand, and were backed by resources that he himself lacked. But the missionary record was not an impressive one, and even those incomparable colonisers of the faith, the Jesuits, had little to show but failure.

In the early days they had put their luckless converts into long white robes, segregated the sexes, and set them to ‘godly labours’, lightened by the chanting of psalms in Latin, as week as mind-developing exercises in mnemonics, and speculative discussions on such topics as the number of angels able to perch on the point of a pin. It was offered as a foretaste of the delights of the Christian heaven, complete with its absence of marrying or giving in marriage. Many of the converts died of melancholy. After a while demoralisation spread to the fathers themselves and some of them went off the rails to the extent of dabbling in the slave trade. When these missionary settlements were finally overrun by the bloodthirsty pioneers and frontiersman from São Paulo, death can hardly have been more than a happy release for the listless and bewildered Indian flock.

When the Indian Protection Service was formed the missionaries of the various Catholic orders were rapidly being outnumbered by nonconformists, mostly from the United States. These were a very different order of man, no longer armed only with hellfire and damnation, but with up-to-date techniques of salesmanship in their approach to the problems of conversion. By 1968 the Jornal de Brasil could state:

In reality, those in command of these Indian Protection posts are North American missionaries – they are in all the posts – and they disfigure the original Indian culture and enforce the acceptance of Protestantism.

Whereas the Catholics for all their disastrous mistakes, had mostly led simple, often austere lives, the nonconformists seemed to see themselves as the representatives of the more ebullient and materialistic brand of the faith. They made a point of installing themselves, wherever they went, in large, well-built stone houses, inevitably equipped with an electric generator and every modern labour-saving device. Some of them even had their own planes. If there were roads they had a car or two, and when they travelled by river they preferred a launch with an outboard engine to the native canoe habitually used by the Catholic fathers.

As soon as Indians were attracted to the neighbourhood, a mission store might be opened, and then the first short step towards the ultimate goal of conversion be taken by the explanation of the value and uses of money, and how with it the Indian could obtain all those goods which it was hoped would become necessary to him. The missionaries are absolutely candid and self-congratulatory about their methods. To hold the Indian, wants must be created and then continually expanded – wants that in such remote parts only the missionary can supply. A greed for unessential trifles must be inculcated and fostered.

The Portuguese verb employed to describe this process is conquistar and it is applied with differentiation to subjection by force or guile. What normally happens is that presents – usually of food – are left where the ‘uncivilised’ Indians can find them. Great patience is called for. It may be years before the tribesmen are won over by repeated overtures, but when it happens the end is in sight. All that remains is to encourage them to move their village into the mission area, and let things take their natural course.

In nine cases out of ten the local landowner has been waiting for the Indians to make such a move – he may have been alerted by the missionary himself – and as soon as it happens he is ready to occupy the tribal land. The Indians are now trapped. They cannot go back, but at the time it seems unimportant, because for a little longer the missionary continues to feed them, although now the matter of conversion will be broached. This usually presents slight difficulty: natural Indian politeness – and in this case gratitude – accomplishes the rest. Whether the Indian understands what it is all about is another matter. He will be asked to go through what he may regard with great sympathy as a rain-making ceremony, as water is splashed about, and formulae repeated in an unknown language. Beyond that it is likely to be a case of let well alone. Any missionary will tell you that an Indian has no capacity for abstract thought. How can he comprehend the mystery and universality of God when the nearest to a deity his own traditions have to offer may be a common tribal ancestor seen as a jaguar or an alligator?

From now on the orders and the prohibitions will flow thick and fast. The innocence of nudity is first to be destroyed, and the Indian who has never worn anything but a beautifully made and decorated penis-sheath to suppress unexpected erections, must now clothe himself from the mission’s store of cast-offs to the instant detriment of his health. He becomes subject to skin diseases, and since in practice clothes once put on are never taken off again, pneumonia is the frequent outcome of allowing clothing to dry on the body after a rainstorm.

The man who has hitherto lived by practising the skills of the hunter and horticulturist – the Indians are devoted and incomparable gardeners of their kind – now finds himself, broom or shovel in hand as an odd-job man about the mission compound. He shrinks visibly within his miserable, dirty clothing, his face becomes puckered and wizened, his body more disease-ridden, his mind more apathetic. There is a terrible testimony to the process in the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture’s handbook on Indians, in which one is photographed genial and smiling on the first day of his arrival from the jungle, and then the same man who by this time appears to be crazy with grief is shown again, ten years later. ‘His expression makes comment unnecessary,’ the caption says. ‘Ninety percent of his people have died of influenza and measles. Little did he imagine the fate that awaited them when they sought their first contact with the whites.’

There is a ring about these stories of enticement down the path to extinction, of the cruel fairytale of children trapped by the witch in the house made of gingerbread and barley sugar. But even the slow decay, the living death of the missionaries’ compound was not the worst that could happen. What could be far more terrible would be the decision of the fazendeiro – as so often happened – to recruit the labour of the Indians whose lands he had invaded, and who are left to starve.

Extract from the atrocity commission’s report:

In his evidence Senhor Jordao Aires said that eight years previously the six hundred Ticuna Indians were brought by Fray Jeremias to his estate. The missionary succeeded in convincing them that the end of the world was about to take place, and Belem was the only place where they would be safe ... Senhor Aires confirmed that when the Indians disobeyed his orders his private police chained them hand and foot. Federal Police Delegate Neves said that some of the Indians thus chained were lepers who had lost their fingers.

Officially it is the Indian Protection Service and 134 of its agents that are on trial, but from all these reports the features of a more sinister personality soon emerge, the fazendeiro – the great landowner – and in his shadow the IPS agent shrinks to a subservient figure, too often corrupted by bribes.

One would have wished to find an English equivalent for this Portuguese word fazendeiro, but there is none. Titles such as landowner or estate owner, which call to mind nothing harsher than the mild despotism of the English class system, will not do. The fazendeiro by European standards is huge in anachronistic power, often the lord of a tropical fief as large as an English county, protected from central authority’s interference by vast distances, traditions of submission, and the absolute silence of his vassals. All the lands he holds – much of which may not even have been explored – have been taken by him or by his ancestors from the Indians, or have been bought from others who have obtained them in this way. In most cases his great fortress-like house, the fazenda, has been built by the labour of the Indian slaves, who have been imprisoned when necessary in its dungeons. In the past a fazendeiro could only survive by his domination of a ferocious environment, and although in these days he will probably have had a university education, he may still sleep with a loaded rifle beside his bed. Lonely fazendas are still occasionally attacked by wild Indians (i.e. Indians with a grievance against the whites), by gold prospectors turned bandit, by downright professional bandits themselves, or by their own mutinous slaves. The fazendeiro defends himself by a bodyguard enrolled from the toughest of his workers – in the backwoods many of them are fugitives from justice.

It has often been hard by ordinary Christian standards for the fazendeiro to be a good man, only too easy for him to degenerate into a Gilles de Raïs, or some murderous and unpredictable Ivan the Terrible of the Amazon forests. It can be Eisenstein’s Thunder Over Mexico complete with the horses galloping over men buried up to their necks – or worse. Some of the stories told about the great houses of Brazil of the last century in their days of respectable slavery and Roman licence bring the imagination to a halt: a male slave accused of some petty crime castrated and burned alive ... a pretty young girl’s teeth ordered by her jealous mistress to be drawn, and her breasts amputated, to be on the safe side ... another, found pregnant, thrown alive into the kitchen furnace.

An extract from the report by the President of last year’s inquiry commission into atrocities against the Indians corrects the complacent viewpoint that we live in milder days.

In the 7th Inspectorate, Paraná, Indians were tortured by grinding the bones of their feet in the angle of two wooden stakes, driven into the ground. Wives took turns with their husbands in applying this torture.

It is alleged, as well, in this investigation, that there were cases of an Indian’s naked body being smeared with honey before leaving him to be bitten to death by ants.

Why all this pointless cruelty? What is it that causes men and women probably of extreme respectability in their everyday lives to torture for the sake of torturing? Montaigne believed that cruelty is the revenge of the weak man for his weakness, a sort of sickly parody of valour. ‘The killing after a victory is usually done by the rabble and baggage officials.’

It is the beginning of the rainy season, and from an altitude of 2,000 feet the forest smokes here and there as if under sporadic bombardment, while the sun sucks up the vapour from the local downpour.

The Mato Grosso seen from the air is supposed to offer a scene of monotonous green, but this is not always so. At this moment, for example, a pitch-black swamp lapped by ivory sands presents itself. It is obscured by shifting feathers of cloud, which part again to show a Cheddar Gorge in lugubrious reds. The forest returns, pitted with lakes which appear to contain not water but brilliant chemical solutions: copper sulphate, gentian violet. The air taxi settles wobbling to a scrubbed patch of earth where vultures flutter like black rags.

All these small towns in this meagre earth are the same. A street of clapboard, tapering off to mud and palm thatch at each end; a general store, a hotel, Laramie-style with men asleep on the veranda; a scarecrow horse with bones about to burst through the hide, tied up in a square yard of shade; hairy pigs; aromatic dust blown up by the hot breeze.

Life is in slow motion and on a small scale. The store sells cigarettes, meticulously bisected if necessary with a razor blade, ladlefuls of mandioca flour, little piles of entrails for soup, purgative pills a half-inch in diameter, and handsomely tooled gun holsters. The customers enter not so much to buy but to be there, wandering through the paperchains of dusty dried fish hanging from the ceiling. They are Indians, but so de-racialised by the climate of boredom and their grubby cotton clothing, that they could be Eskimos or Vietnamese. They have the expression of men gazing, narrow-eyed, into crystal balls, and they speak in childish voices of great sweetness. Like Indians everywhere, the smallest intake of alcohol produces an instant deadly change.

The only entertainment the town offers is a cartomancer, operating largely on a barter basis. He tells fortunes in a negative but realistic way, concerned not so much with good luck, but the avoidance of bad. All the children’s eyes are rimmed with torpid, hardly moving flies. The fazenda, some miles away, has absorbed everything; owns the whole town, even the main street itself.

This is a place where cruelty is supposed to have happened, but the surface of things has been patched and renovated and the aroma of atrocity has dispersed. Everything can now be explained away as examples of extreme exaggeration, or the malice of political enemies, and all the witnesses for the defence have been mustered. Finally, the everyday violences of a violent country are quoted to remind one that this is not Europe.

Senhor Fulano lives with his family in three rooms in one of the few brick-built houses. His position is ambiguous. An ex-Indian Protection Service agent, he has been cleared of financial malpractices, and hopes shortly for employment in the new Foundation. He has an Abyssinian face with melancholy, faintly disdainful eyes, a high Nilotic forehead, and a delicate Semite nose. He is proud of the fact that his father was half Negro, half Jewish; a trader who captured in marriage a robust girl from one of the Indian tribes.

‘Not all fazendeiros are bad,’ Fulano says. ‘Far from it. On the contrary, the majority are good men. People are jealous of their success, and they are on the look-out for a way to damage them.

‘In the case you mention the man was a thief and a troublemaker. As a punishment he was locked in the shed, nothing more. He was drunk, you understand, and he set fire to the shed himself. He died in the fire, yes, but the doctor certified accidental death. There was no case for a police inquiry. In thirty years’ of service I have only seen one instance of violence – if you wish to call it violence. The Indians were drunk with cachaça again, and they attacked the post. They were given a chance by firing over their heads, but it didn’t stop them. They were mad with liquor. What could we do? There’s no blood on my hands.’ He holds them up as if a confirmation. They are small and well cared for with pale, pinkish palms. His wife rattles about out of sight in the scullery of their tiny flat. A picture of the President hangs on the wall, and another of Fulano’s little girl dressed for her first communion, and there is no evidence in the cheap, ugly furniture that Senhor Fulano has been able to feather his nest to any useful extent.

He joined the service out of a sense of vocation, he says. ‘We were all young and idealistic. They paid us less than they paid a post man, but nobody gave any thought to that. We were going to dedicate our lives to the service of our less fortunate fellow men. If anyone happened to live in Rio de Janeiro, the Minister himself would see him when he was posted, shaking hands with him and wish him good luck. I happened to be a country boy, but my friends hired a band to see me off to the station. Everybody insisted in giving me a present. I had so many lace handkerchiefs I could have opened a shop. There was a lot of prestige in being in the service in those days.’

There are three whitish, glossy pockmarks in the slope of each cheek under the sad, Amharic eyes, and it is difficult not to watch them. He shakes his head. ‘No one would believe the conditions some of us lived under. They used to show you photographs of the kind of place where you’d be working: a house with a veranda, the school and the dispensary. When I went to my first post I wept like a child when I saw it. The journey took a month and in the meanwhile the man I was supposed to be assisting had died of the smallpox. I remember the first thing I saw was a dead Indian in the water where they tied up the boat. I’d hit a measles epidemic. Half the roof of the house had caved in. There never had been a school, and there wasn’t a bottle of aspirin in the place. When the sun went down the mosquitoes were so thick, they were on your skin like fur.’

He finds an album of press-cuttings in which are recorded the meagre occasions of his life. A picture shows him in dark suit and stiff collar receiving a certificate and the congratulations of a politician for his work as a civiliser. In another he is shown posing at the side of Miss Pernambuco 1952, and in another he is a paternal presence at a ceremony when a newly pacified tribe are to put on their first clothing. There are ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures of the tribal women, first naked and then in jumpers and skirts, not only changed but facially unrecognisable from one moment to the next, as if some malignant spell had been laid upon them as they wriggled into the shapeless garments. The few cuttings, which I scan through out of politeness, speak of Senhor Fulano as the pattern of self-abnegation, and the words servicio and devoçao constantly reappear. ‘My trifling pay was only one hundred cruzeiros a month,’ he says, ‘and it was sometimes up to six months overdue. In just the first year I caught measles, jaundice and malaria three times. If it hadn’t been for the fazendeiro, I’d have died. He looked after me like a father. He was a man of the greatest possible principles, and among many other benefactions he gave 100,000 cruzerios to a church in Salvador. I see now that his son has been formally charged with invading Indian lands. All I can say to that is, what the Indians would do without him, I don’t know.’

Fulano is nothing if not loyal. ‘Fazendeiros are no different from anyone else,’ he says. ‘They try to make out they’re monsters these days. You mustn’t believe all you read.’

It was certain that no one would be found now in this town to contradict him.

For a half-century rubber had been the great destroyer of the Indian, and then suddenly it changed to speculation in land. Rumour spread of huge mineral resources awaiting exploitation in the million square miles that were inaccessible until recently – and the great speculative rush was on. Nowhere, however remote, however sketchily mapped, was secure from the surveyors, who were sent out to measure out the claims of the politicians, the real-estate companies and the fazendeiros. Back in São Paulo, the headquarters of the land boom, the grileiro – specialist in shady land deals – went into secret partnerships with his friend in the Government, who was well positioned to see that the deals went through. A great deal of this apparently empty land was only empty to the extent that it contained no white settlements, and the map-makers had not yet put in the rivers and the mountains. There might well be Indians there – nobody knew until it had been explored – but this possibility introduced only a slight inconvenience. In theory the undisturbed possession of all land occupied by Indians is guaranteed to them by the Brazilian constitution, but if it can be shown that Indian land has been abandoned it reverts to the Government, after which it can be sold in the ordinary way. The grileiro’s task is to discover or manufacture evidence that such land is no longer in occupation – a problem, if sincerely confronted, complicated by the fact that most Indians are semi-nomadic, cultivating crops in one area during the period of the summer rains, then moving elsewhere to hunt and fish during the dry winter season.

A short cut to the solution of the problem is simply to drive the Indians out. Other grileiros quite simply ignore its existence, offering land to the gullible by map reference, sight unseen, and hoping to be able to settle the legal difficulties by political manipulations at some later date.

The grileiro with his manoeuvrings behind the scenes was kept under some control while President João Goulart was in power, and it finally became clear to the big-scale land speculators that they were going to get nowhere until they got a new President. Goulart, although a rich landowner himself, held the opinion that Brazil would never occupy the place in the Western Hemisphere to which its colossal size and resources entitled it, while it limped along in its feudalistic way with an 86 percent illiteracy figure and the land in the hands of an infinitesimally small minority, many of which made no effort to develop it in any way. The remedy he proposed was to redistribute 3 percent of privately owned land, but also – what was far more serious – he announced the resuscitation of an old law permitting the Government to nationalise land up to six miles in depth on each side of the national means of communication – roads, railways and canals.

This would have been a death blow to the speculators, who hoped to resell their land at many times the price they had paid, as soon as it was made accessible by the building of roads. One such firm had advertised 100,000 acres of land for sale in the English Press. The land was offered in 100-acre minimum lots at £5 an acre. An initial purchase of land had already been sold, the company announced, ‘mainly to investment houses and trusts, insurance companies and a number of syndicates.’ A charter flight would be arranged for buyers from Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Liverpool, and representatives of Kenya farmers who had already bought 50,000 acres. ‘There is little hope,’ said the promotion literature, ‘of any return from the purchase of the land for a few years yet.’

But in 1964 the speculative prospects brightened enormously when a coup d’état was staged to depose the troublesome Goulart, and the land rush could go ahead. A promotional assault was launched on the United States market with lavishly produced and cunningly worded brochures offering glamour as well as profit, being phrased in the poetic style of American car advertisements. Amazon Adventure Estates were offered, and there were allusions to monkeys and macaws and the occult glitter of gems in the banks of mighty rivers sailed by the ships of Orellana. They had some success. Several film stars took a gamble in the Mato Grosso. In April 1968, in fact, a Brazilian deputy, Haroldo Veloso, revealed that most of the area of the mouth of the Amazon had passed into the hands of foreigners. He mentioned that Prince Rainier of Monaco had bought land in the Mato Grosso twelve times larger than the principality. Someone, presumably stabbing with a pencil at a map, had picked up the highest mountain in Brazil – the Pico de Nieblina – for a song, although it would have taken a properly equipped expedition a matter of weeks to reach it.

This was doomsday for the tribes who had been pacified and settled in areas where they could be conveniently dealt with. Down in the plains on the frontiers with Paraguay it was the end of the road for the Kadiweus. In 1865 in the war against Paraguay they had taken their spears and ridden naked, barebacked, but impeccably painted – a fantastic Charge of the Light Brigade, at the head of the Brazilian army – to rout the cavalry of the psychopathic Paraguayan dictator Solano Lopez. For their aid in the war the Emperor Pedro II had received the principal chief, clad for the occasion in a loincloth sewn with precious stones, and granted the Kadiweu nation in perpetuity two million acres of the borderland. Here these Spartans of the West were reduced now to two hundred survivors, working as the cowhands of fazendeiros who had taken all their lands.

It was also doomsday for Lévi-Strauss’s Bororos. The great anthropologist had lived for several years among them in the 1930s, and they had led him to the conclusions of ‘structural anthropology’, including the proposition that ‘a primitive people is not a backward or retarded people, indeed it may possess a genius for invention or action that leaves the achievements of civilised people far behind.’ He had said of the Bororos, ‘few people are so profoundly religious ... few possess a metaphysical system of such complexity. Their spiritual beliefs and everyday activities are inextricably mixed.’ They had been living for some years now far from the complicated villages where Lévi-Strauss studied them, in the Teresa Cristina reserve in the South Mato Grosso, given them ‘in perpetuity’, as ever, in tribute to the memory of the great Marshall Rondon, who had been part-Bororo himself.

Life in the reserve was far from happy for the Bororos. They were hunters, and fishermen, and in their way excellent agriculturists, but the reserve was small, and there was no game left and the rivers in the area had been illegally fished-out by commercial firms operating on a big scale, and there was no room to practise cultivation in the old-fashioned semi-nomadic way. The Government had tried to turn them into cattle-raisers, but they knew nothing of cattle. Many of the cows were quietly sold off by agents of the Indian Protection Service, who pocketed the money. Others – as the Bororos had no idea of being building corrals – wandered out of the reservation before being impounded by neighbouring fazendeiros. The Indians ate the few cows that remained before they could die of disease or starvation, after which they were reduced to the normal diet of hard times – lizards, locusts and snakes – plus an occasional handout of food from one of the missions.

They also suffered from the great emptiness and aimlessness of the Indian whose traditional culture has been destroyed. The missionaries, upon whom they were wretchedly dependent, forbade dancing, singing or smoking, and while they accepted with inbred stoicism this attack on the principle of pleasure, there was a fourth prohibition against which they continually rebelled, but in vain.

The Indians are obsessed by their relationship with the dead, and by the condition of the souls of the dead in the afterlife – a concern reflected in the manner of the ancient Egyptians by the most elaborate funerary rites: orgies of grief and intoxication, sometimes lasting for days. The Bororos, seemingly unable to part with their dead, bury them twice, and the custom is at the emotional basis of their lives. In the first instance – as if in hope of some miraculous revival – the body is placed in a temporary grave, in the centre of the village, and covered with branches. When decomposition is advanced, the flesh is removed from the bones, which are painted and lovingly adorned with feathers, after which final burial takes place in the depths of the forest. The outlawing of this custom by an American missionary reduced the Bororos to despair, but the missionary was able to persuade the local police to enforce the ban, and the party of half-starved tribesmen who dragged themselves two hundred miles on foot to the State capital and presented themselves, weeping, to the commissario were turned away.

Final catastrophe followed the devolution by the Federal Government of certain of its powers – particularly those relating to the ownership and sale of land – to the Legislative Assembly of the Mato Grosso State. This at once invoked a law by which land that, after a certain time limit, had not been legally measured and demarcated, reverted to the Government. It was a legal device which saddled Indians, many of whom did not even realise that they were living in Brazil, with the responsibility of employing lawyers to look after their interests. It had been employed once before, and with additional refinements of trickery, in an attempt to snatch away the last of the land of the unfortunate Kadiweus. On this occasion it seems that only two copies of the official publication recording the enactment were available, one of which had been lodged in the State archives, and the other taken the same day to the reserve by the persons proposing to share the land between them.

Hardly less haste was shown in the occupation of the Teresa Cristina reserve. It was a muddled, untidy operation, and it finally turned out that considerably more land had been sold on paper than the actual area of the reserve. This was before the final demoralisation and collapse of the Indian Protection Service. Local officials not only challenged the legality of the sale but called in vain for State troops to be sent to repel an invasion of fazendeiros, who were supported by their private armies carrying sub-machineguns.

The state of affairs that had come to pass at Teresa Cristina only five years later, in 1968, is depicted in the testimony of a Bororo Indian girl.

There were two fazendas, one called Teresa, where the Indians worked as slaves. They took me from my mother when I was a child. Afterwards I heard that they hung my mother up all night.... She was very ill and I wanted to see her before she died.... When I got back they thrashed me with a raw-hide whip.... They prostituted the Indian girls.... One day the IPS agent called an old carpenter and told him to make an oven for the farmhouse. When the carpenter had finished the agent asked him what he wanted for doing the job. The carpenter said he wanted an Indian girl, and the agent took him to the school and told him to choose one. No one saw or heard any more of her.... Not even the children escaped. From two years of age they worked under the whip.... There was a mill for crushing the cane, and to save the horses they used four children to turn the mill. They forced the Indian Ottaviano to beat his own mother.... The Indians were used for target practice.

Thus were the Indians disarmed, betrayed, and hustled down the path towards final extinction. Yet in the heart of the Mato Grosso and the Amazon forests, there were tribes that still held out. Classified by the Government manual on Indians as isolados, they are described as those that possess the greatest physical vigour. Nobody knows how many such tribes there are. There may be three hundred or more with a total population of fifty thousand, including tiny, self-contained and apparently indestructible nations having their own completely separate language, organisation and customs. Some of these people are giants with herculean limbs, armed with immense longbows of the kind an archer at Crécy might have used. A few groups are ethnically mysterious with blue eyes and fairish hair, provokers of wild theories among Amazonian travellers, that there is one tribe supposed by some to have migrated to these forests some two thousand years ago from the island of Hokkaido in Japan. One common factor unites them all; a brilliant fitness for survival – until now. For 400 years they have avoided the slavers and lived through the epidemics. They have armed themselves with constant alertness. They have been ready to embrace a new tactical nomadism. They have made distrust the greatest of their virtues. Above all, the chieftains have had the intelligence and the strength to reject those deadly offerings left outside their villages by which the whites seek first to buy their friendship, then take away their freedom.

The Cintas Largas were one such tribe living in magnificent if precarious isolation in the upper reaches of the Aripuaná River. There were about five hundred of them, occupying several villages.

They used stone axes, tipped their arrows with curare, caught small fish, played four-feet long flutes made from gigantic bamboos, and celebrated two great annual feasts: one of the initiation of young girls at puberty, and the other of the dead. At both of these they were said to use some unknown herbal concoction to produce ritual drunkenness. They were in a region still dependent for its meagre revenues on wild rubber, and this exposed them to routine attacks by rubber tappers, against whom they had learned to defend themselves. Their tragedy was that deposits of rare metals were being found in the area. What these metals were, it was not clear. Some sort of a security blackout had been imposed, only fitfully penetrated by vague news reports of the activities of American and European companies, and of the smuggling of planeloads of the said rare metals back to the United States.

David St Clair in his book The Mighty Mighty Amazon mentions the existence of companies who specialised in dealing with tribes when their presence came to be considered a nuisance, attacking their villages with famished dogs, and shooting down everyone who tried to escape. Such expeditions depended for their success on the assistance of a navigable river which would carry the attacking party to within striking distance of the village or villages to be destroyed. The Beiços de Pau had been reached in this way and dealt with by the gifts of foodstuffs mixed with poisons, but the two inches on the small-scale map of Brazil separating these two neighbouring tribes contained unexplored mountain ranges, and the single river ran in the wrong direction. The Cintas Largas, then, remained for the time being out of reach. In 1962, a missionary, John Dornstander, had reached and made an attempt to pacify them but he had given them up as a bad job.

The plans for disposing of the Cintas Largas were laid in Aripuaná. This small festering tropical version of Dodge City in 1860 has the face and physique of all such Latin-American hellholes, populated by hopeless men who remain there simply because for one reason or other, they cannot leave. A row of wooden huts on stilts stands in the hard sunshine down by the river. Swollen-bellied children squat to delouse each other; dogs eat excrement; vultures limp and balance on the edge of a ditch full of black sewage; the driver of an oxcart urges on the animal wreckage of hide and bones by jabbing with a stick under its tail. Everyone carries a gun. Cachaça offers oblivion at a shilling a pint, but boredom rots the mind. There are two classes: those who impose suffering, and the utterly servile. In this case nine-tenths of the working population are rubber tappers, and most of them fugitives from justice.

A cheap and sometimes effective ruse – besides being the quite normal procedure where a tribe’s villages are beyond reach – is to bribe other Indians to attack them; and this was tried in the first instance with the Cintas Largas. The Kayabis, neighbours both of the Cintas Largas and the Beiços de Pau, had been dispersed when the State of Mato Grosso sold their land to various commercial enterprises, part of the tribe migrating to a distant range of mountains, while a small group that had split off remained in this Aripuaná area, where it lived in destitution. This group took the food and guns that they were offered in down-payment, and then decamped in the opposite direction and no more was seen of them.

Later a garimpa – an organised body of diamond prospectors – appeared in the neighbourhood. They were all in very bad shape through malnutritional disorders. They had attacked an Indian village and had been beaten off and then ambushed, and several of them were wounded. The intention had been to capture at least one woman, not only for sexual uses, but as a source of supply of the fresh female urine believed to be a certain cure for the infected sores from which the garimpeiros habitually suffer, and which are caused by the stingrays abounding in the rivers in which they work. Garimpeiros are organised under a captain who supplies their food and equipment, and to whom they are bound to sell their diamonds – under pain of being abandoned in the forest to die of starvation. Like the rubber tappers – who are their traditional enemies – they are mostly wanted by the police. The feud existing between these two types of desperado is based on the rubber tappers’ habit of stalking and shooting the lonely garimpeiro, in the hope that he may be found with a diamond or two. In this case emissaries arranged a truce, and the garimpeiros were brought into town, and given food; a company doctor patched up the wounded men. Common action against the Cintas Largas was then proposed, and the captain fell in with the suggestion and agreed to detach six men for this purpose as soon as everyone was fully rested. In the condition in which he found himself, he may have been ready to agree to anything, but by the time the garimpeiros had put on a little flesh and their wounds had cleared up, there was an abrupt cooling in the climate of amity. Aripuaná was not a big enough town to contain two such trigger-happy personalities as the garimpa captain and the overseer of the rubber tappers. For a while the poverty-stricken rubber tappers put up with it, while the affluent garimpeiros swaggered in the bars, and monopolised the town’s prostitutes. Then, inevitably, the entente cordiale foundered in gunplay.

In 1963 a series of expeditions were now organised under the leadership of Francisco de Brito, general overseer of the rubber extraction firm of Arruda Junqueira of Juina-Mirim near Aripuaná, on the river Juruana.

De Brito was a legendary monster who kept order among the ruffians he commanded by a .45 automatic and a five-foot tapir-hide whip. He made cruel fun of the Indians, and when one was captured he was taken on what was known as ‘the visit to the dentist’, being ordered to ‘open wide’ whereupon De Brito drew a pistol and shot him through his mouth. There was a lively competition among the rubber men for the title of champion Indian killer, and although this was claimed by De Brito, local opinion was that his score was bettered by one of his underlings who specialised in casual sniping from the riverbanks.

The expeditions mounted by De Brito were successful in clearing the Cintas Largas from an area, insignificant by Brazilian standards, although about half as big as England’s southern counties; but there remained a large village considered inaccessible on foot or by canoe, and it was decided to attack this by plane. At this stage it is evident that a better type of brain began to interest itself in these operations, and whoever planned the air-attack was clearly at some pains to find out all he could about the customs of the Cintas Largas.

It was seen as essential to produce the maximum number of casualties in one single, devastating attack, at a time when as many Indians as possible would be present in the village, and an expert was found to advise that this could best be done at the annual feast of the Quarup. This great ceremony lasts for a day and a night, and under one name or another it is conducted by almost all the Indian tribes whose culture has not been destroyed. The Quarup is a theatrical representation of the legends of creation interwoven with those of the tribe itself, both a mystery play and a family reunion attended not only by the living but the ancestral spirits. These appear as dancers in masquerade, to be consulted on immediate problems, to comfort the mourners, to testify that not even death can disrupt the unity of the tribe.

A Cessna light plane used for ordinary commercial services was hired for the attack, and its normal pilot replaced by an adventurer of mixed Italian-Japanese birth. It was loaded with sticks of dynamite – ‘bananas’ they are called in Brazil – and took off from a jungle airstrip near Aripuaná. The Cessna arrived over the village at about midday. The Indians had been preparing themselves all night by prayer and singing, and now they were all gathered in the open space in the village’s centre. On the first run, packets of sugar were dropped to calm the fears of those who had scattered and run for shelter at the sight of the plane. They had opened the packets and were tasting the sugar ten minutes later when it returned to carry out the attack. No one has ever been able to find out how many Indians were killed, because the bodies were buried in the bank of the river and the village deserted.

But even this solution proved not to be final. Survivors had been spotted from the air and were reported to be building fresh settlements in the upper reaches of the Aripuaná, and once again De Brito got together an overland force.

They were to be led, in canoes, by one Chico, a De Brito underling. The full story of what happened was described by a member of the force, Ataide Pereira, who, troubled by his conscience and also by the fact that he had never been paid the fifteen dollars promised him for his bloody deeds, went to confess them to a Padre Edgar Smith, a Jesuit priest, who took his statement on a tape recorder and then handed the tape to the Indian Protection Service.

‘We went by launch up the Juruana,’ Ataide says. ‘There were six of us, men of experience, commanded by Chico, who used to shove his tommy-gun in your direction whenever he gave you an order!’ (Chico, it was to turn out, was no mere average sadist of the Brazilian Badlands. For this kind of Latin American – and they have been the executioners of so many revolutions – the ultimate excitement lies in the maniac use of the machete on the victims, and it was to use this machete that Chico had gone on this expedition.) ‘It took a good many days upstream to the Serra do Norte. After that we lost ourselves in the woods, although Chico had brought a Japanese compass with us. In the end the plane found us. It was the same plane they used to massacre the Indians, and they threw us down some provisions and ammunition. After that we went on for five days. Then we ran out of food again. We came across an Indian village that had been wiped out by a gang led by a gunman called Tenente, and we dug up some of the Indians’ mandioca for food and caught a few small fish. By this time we were fed up and some of us wanted to go back, but Chico said he’d kill anybody who tried to desert. It was another five days after that before we saw any smoke. Even then the Cintas Largas were days away. We were all pretty scared of each other. In this kind of place people shoot each other and get shot, you might say without knowing why.

‘When they drill a hole in you, they have this habit of sticking an Indian arrow in the wound, to put the blame on the Indians.’

This expedition breathed in the air of fear. Ataide reports that there were diamonds and gold in all the rivers, and the shadow of the garimpeiro stalked them from behind every rock and tree. A violent death would claim most of these men sooner or later. Premature middle age brought on by endless fever, malnutrition, exhaustion, hopelessness and drink overtook the rubber tappers in their late twenties, and few lived to see their thirtieth birthday. An infection turning to gangrene or blood-poisoning would carry them off; or they would die in an ugly fashion, paralysed, blind and mad from some obscure tropical disease; or they would simply kill each other in a sudden neurotic outburst of hate provoked by nothing in particular – for a bet, or in a brawl over some sickly prostitute picked up at a village dance.

Hacking their way through this sunless forest a month or more’s march from the dreadful barracks that was their home, they were dependent for survival on the psychopathic Chico and his Japanese compass. It was the beginning of the rainy season when, after a morning of choking heat, sudden storms would drench them every afternoon. They were plagued with freshly hatched insects, worst of all the myriads of almost invisible piums that burrow into the skin to gorge themselves with blood, and against which the only defence is a coating of grime on every exposed part of the body. Some of the men were blistered from the burning sap squirted on them from the lianas they were chopping

‘We were handpicked for the job,’ Ataide says, with a lacklustre attempt at esprit de corps, ‘as quiet as any Indian party when it came to slipping in and out of trees. When we got to Cintas Largas country there were no more fires and no talking. As soon as we spotted their village we made a stop for the night. We got up before dawn, then we dragged ourselves yard by yard through the underbrush till we were in range, and after that we waited for the sun to come up.

‘As soon as it was light the Indians all came out and started to work on some huts they were building. Chico had given me the job of seeking out the chief and killing him. I noticed there was one of these Indians who wasn’t doing any work. All he did was to lean on a rock and boss the others about, and this gave me the idea he must be the man we were after. I told Chico and he said, “Take care of him, and leave the rest to me,” and I got him in the chest with the first shot. I was supposed to be the marksman of the team, and although I only have an ancient carbine, I can safely say I never miss. Chico gave the chief a burst with his tommy-gun to make sure, and after that he let the rest of them have it ... all the other fellows had to do was to finish off anyone who showed signs of life.

‘What I’m coming to now is brutal, and I was all against it. There was a young Indian girl they didn’t shoot, with a kid of about five in one hand, yelling his head off. Chico started after her and I told him to hold it, and he said, “All these bastards have to be knocked off.” I said, “Look, you can’t do that – what are the padres going to say about it when you get back?” He just wouldn’t listen. He shot the kid through the head with his .45, then he grabbed hold of the woman – who by the way was very pretty. “Be reasonable,” I said. “Why do you have to kill her?” In my view, apart from anything else, it was a waste. “What’s wrong with giving her to the boys?” I said. “They haven’t set eyes on a woman for six weeks. Or failing that we could take her back with us and make a present of her to De Brito. There’s no harm in keeping in with him.” All he said was, “If any man wants a woman he can go and look for her in the forest.”

‘We all thought he’d gone off his head, and we were pretty scared of him. He tied the Indian girl up and hung her head downwards from a tree, legs apart, and chopped her in half right down the middle with his machete. Almost with a single stroke I’d say. The village was like a slaughterhouse. He calmed down after he’d cut the woman up, then told us to burn down all the huts and throw the bodies into the river. After that we grabbed our things and started back. We kept going until nightfall and we took care to cover our tracks. If the Indians had found us it wouldn’t have been much use trying to kid them that we were just ordinary backwoodsmen. It took us six weeks to find the Cintas Largas, and about a week to get back. I want to say now that personally I’ve nothing against Indians. Chico found some minerals and took them back to keep the company pleased. The fact is the Indians are sitting on valuable land and doing nothing with it. They’ve got a way of finding the best plantation land and there’s all these valuable minerals about too. They have to be persuaded to go, and if all else fails, well then, it has to be force.’

De Brito, the man who organised this expedition, was to die within a year of it in the most horrific circumstances. When he found cause for complaint in one of his men, he would normally tie him up and thrash him until the blood ran down and squelched into the man’s boots, but in an aggravated case he would have one of his henchmen use the whip while he raped the culprit’s wife as the punishment was being inflicted. An Italian called Cavalcanti, who tried to attack the overseer after receiving the more serious punishment, was promptly shot dead and his body burned. A revolt of the rubber tappers followed in which nine men were killed. De Brito when cornered was like Rasputin, very difficult to disable, and absorbed several bullets and a thrust in the stomach with a machete before he went down. After this he was stripped, the bowels plugged back with a tampon of straw, then dragged alive into the open and left ‘for the ants’.

How many Indian hunts of the kind mounted against the Cintas Largas must have gone on unnoticed in the past, condemned at worst as a necessary evil? Ataide speaks of them as if they were commonplace, and the likelihood is confirmed by a statement, made to the police inspector of the 3rd Divisional Area of Cuiabá Salgado who investigated the case, by a Padre Valdemar Veber. The Padre said, ‘It is not the first time that the firm of Arruda Junqueira has committed crimes against the Indians. A number of expeditions have been organised in the past. This firm acts as a cover for other undertakings who are interested in acquiring land, or who plan to exploit the rich mineral deposits existing in this area.’

When one considers the miasmic climate of subjection in which these remote rubber baronies operate, in which the voice raised in protest can be instantly suffocated, and as many false witnesses as required created at the lifting of a finger, it seems extraordinary that police action could ever have been contemplated against Arruda Junqueira. It appears even more so when one surveys the sparse judicial resources of the area.

Denunciations by the hundred, of the kind made by Atiade, lie forgotten in police files, simply because the police have learned not to waste their strength in attempting the impossible. Nine major crimes out of ten probably never come to light. The problem of the disposal of the body – so powerful a deterrent to murder – does not exist where it can be thrown into the nearest stream, where – if a cayman does not dispose of it – the piranhás can reduce it to a clean skeleton in a matter of minutes.